How My Son and I Built a Racing Empire with 4847 Words (Using AI)

The 4847 word specification that built MySimRig.nl in an afternoon

It started on one of those Dutch afternoons that can’t decide between drizzle and despair.

The sky sagged low, the air smelled faintly of rubber and burnt coffee, and my office looked like a garage that had lost faith in tidiness.

A half-assembled pedal set leaned against my MacBook. The 3D printer in the corner whined through another failed bracket, a small monument to optimistic engineering.

That’s when my son appeared in the doorway, laptop under his arm, wearing the look of a man preparing to file a grievance.

“Dad,” he said. I didn’t look up. I knew that tone. “Wix sucks.”

No context. No warm-up. Just a declaration of war.

He dropped the laptop on my desk. MySimRig.nl glowed on the screen, not a bad site, exactly, just one that looked like it had been designed inside a padded cell. Clean, polite, but utterly lifeless. Every pixel screamed compromise.

“I can’t do anything with this,” he said. “Every time I fix one thing, another breaks. I want to add a calculator, or a product list, or something actually useful, and it just tells me no.”

I sipped my coffee. “So… business as usual.”

He rolled his eyes. “No, seriously. It’s holding me back.”

That phrase again. I’d heard it before, T-shirts, hot sauce, drop-shipping. Each venture began with fireworks and ended with silence once the grind kicked in.

He wasn’t short on ideas. He was short on endurance.

The Wix breaking point

But this time, something was different.

We’re a racing family. The kind that debates tire wear over dinner and treats qualifying sessions like national holidays. I’ve spent more hours tuning virtual setups than most people spend watching Netflix. Our living room has more cables than furniture.

He grew up in that chaos, surrounded by pedals, rigs, telemetry charts, and the low hum of simulated engines. And now, finally, he wanted to build something from it, a site that spoke to sim racers the way only another racer could.

Unlike his earlier schemes, this one had depth. He works in IT support, a job that forces you to learn just enough about everything. He could debug, deploy, and curse at servers like the rest of us. Not a developer, but close enough to be dangerous.

“So what do you actually want it to do?” I asked.

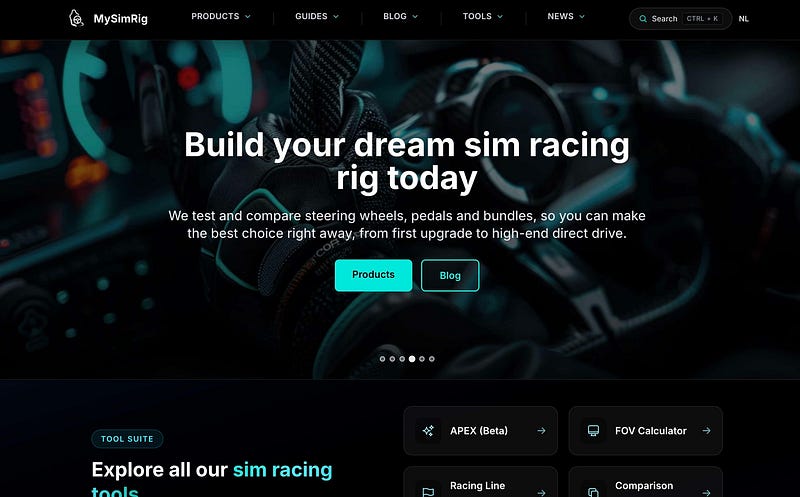

He turned the laptop toward me. “I want it to feel real. Custom FOV calculators. Proper affiliate links. Clean design. None of that prefab junk. I want people to visit and think, this guy actually races.”

The printer beeped again, another failed bracket. The perfect metaphor.

He smirked. “You’re always talking about AI coding agents. Can’t one of them build this?”

I leaned back. I had three half-finished apps, a full-time job, and a Medium draft silently judging me every morning. I didn’t have time for another side project, especially not one destined to become mine.

But something in his tone stopped me.

This wasn’t another get-rich scheme. This was frustration. The kind that comes when imagination outgrows the tools at hand.

I didn’t say yes that afternoon. We just sat there, him scrolling through broken layouts, me pretending to care about the printer. But the spark was already lit.

Maybe it was the way he talked about field-of-view angles like a poet, or the quiet precision in his plan for affiliate tracking. He wasn’t chasing money anymore.

And I knew, in that quiet way fathers sometimes do, that I’d give in. Not because he needed help, but because for the first time, his world of racing and my world of code had finally lined up on the same starting grid.

I didn’t know it then, but MySimRig.nl wouldn’t just be his next side project. It would be the first thing we’d ever truly build together.

Building with machines that almost understand

The specification took three hours to write. Not because the AI was slow, but because every question forced a decision.

“What type of site are you building?” the AI asked first.

My son leaned over my shoulder. “Tell it e-commerce.”

I typed: “Affiliate marketing site for sim racing hardware.”

“No, e-commerce sounds better.”

“E-commerce means inventory. Shipping. Returns. You want to hold stock?”

He considered this for exactly two seconds. “Affiliate marketing site.”

That’s how it starts. Not with code, but with clarity. The AI doesn’t care if you call yourself an e-commerce empire or an affiliate blog. But the code it generates will. Every lie you tell in the specification compounds into technical debt later.

3 hours of questions, 12 minutes of code

The prompt I use forces the AI to ask one question at a time. I learned this after watching ChatGPT write three paragraphs of assumptions that took longer to correct than starting over.

I start every new project with this prompt:

I've got an idea I want to talk through with you.

I'd like you to help me turn it into a fully formed design and spec

(and eventually an implementation plan)

We're starting off completely from scratch, ask me questions, one at a time,

to help refine the idea.

Ideally, the questions would be multiple choice, but open-ended questions

are OK, too. Don't forget: only one question per message.

Once you believe you understand what we're doing, stop and describe the

design to me, in sections of maybe 200-300 words at a time, asking after

each section whether it looks right so far.Now it asks, I answer, it asks again. Like teaching someone over the phone.

“Should the site support multiple languages?”

“Static site generator or dynamic application?”

“How will content be managed?”

Each question carved away ambiguity. My son wanted “everything modern.” The AI needed to know if that meant React with seventeen dependencies or Astro with Markdown files.

We chose Astro. Not because it’s trendy, but because my son knows Markdown and hates databases.

After twenty-three questions, the AI said it understood. Then it wrote the first section of the specification and asked if it looked right.

It didn’t.

The AI had imagined a complex product database with real-time pricing updates. We wanted simple Markdown files with affiliate links.

To a traditional developer, building an e-commerce site without a database sounds insane. But we realized we weren’t building Amazon, we were building a library.

We didn’t need to track live inventory or manage user sessions. We needed speed and security. By using simple Markdown text files instead of a heavy database, the site became unhackable and practically free to host.

If we need to update a product, we don’t wrestle with a slow admin panel, we just edit a text file. It wasn’t a technical compromise; it was a strategic shortcut.

The AI suggested user accounts and wishlists. We needed a static site that builds in thirty seconds.

This is the part nobody mentions about AI development. The machine doesn’t know your constraints. It doesn’t know you’re building this on weekends. It doesn’t know your son will lose interest if deployment requires Kubernetes.

So we corrected. Simplified. Stripped features that sounded good but would never ship. The AI rewrote. We corrected again.

By the fourth iteration, the specification started reflecting reality: A static site built with Astro. Content in Markdown. Images in folders. Deploy via Docker because I already had Traefik running on my VPS. Dark theme with teal accents because that’s what racers expect.

The final specification

The final specification ran 4847 words. Every decision documented. No ambiguity about what “modern” meant. No confusion about “professional looking.” Just specific, buildable requirements.

Read the actual MySim Rig specification on GitHub

I created a new GitHub repository. Added the specification to a /specs folder. Committed. Then opened Claude Code in the terminal.

After Claude code started, I typed:

“Read the specification in the specs folder and create a detailed implementation plan split into phases.”

The specification is the product (not the code)

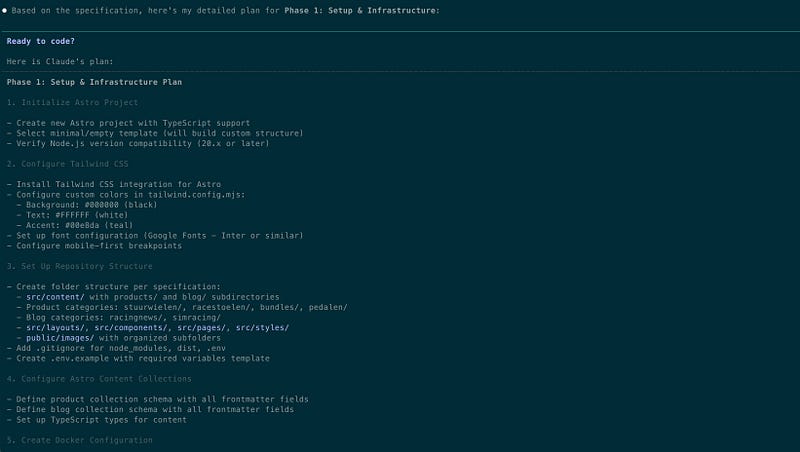

Claude Code read all 4847 words. Then it wrote an implementation plan that split the project into eight phases.

Setup and infrastructure first. Design and layout second. Core features third. Each phase with specific tasks, acceptance criteria, and dependencies.

This wasn’t AI magic. This was AI reading documentation I’d spent three hours writing. The quality of the plan matched the quality of the specification.

When I’d been vague about the carousel behavior, the plan was vague. When I’d been specific about the Docker configuration, the plan included the exact labels for Traefik routing.

“Create a detailed plan for Phase 1,” I typed.

Claude Code expanded Phase 1 into fourteen specific tasks.

Initialize Astro project. Configure Tailwind. Create folder structure. Each task included the exact commands to run, the files to create, the configurations to add.

My son watched the plan generate. “It actually understands Docker?”

“It understands what I told it about Docker.”

“But it knows the Traefik labels.”

“It knows the Traefik labels I put in the specification.”

This is what matters about AI development tools. They don’t eliminate expertise. They multiply it. Every specific detail in your specification becomes ten specific details in the implementation.

Every vague requirement becomes ten interpretations you’ll need to fix.

Claude Code then asked “Would you like to proceed?”

I selected: ❯ 1. Yes, and auto-accept edits

Claude Code created seven files in forty seconds. Package.json with the exact dependencies. Dockerfile with multi-stage builds. docker-compose.yml with the complete Traefik configuration. The folder structure exactly as specified.

My son pulled his chair closer. “How does it know our VPS uses the web network?”

I scrolled up to the specification. Line 247: networks: web (external: true).

“You told it everything?”

“Everything that mattered.”

The first phase took twelve minutes to implement. Not because AI is fast, but because three hours of specification meant twelve minutes of execution instead of twelve hours of debugging.

The AI didn’t need to guess if we wanted CSS-in-JS or Tailwind. It didn’t need to assume our Docker network configuration. It just built what we’d specified.

By the end of that afternoon, we had a dark-themed site with teal accents running on localhost. The carousel worked. The navigation collapsed properly on mobile. The Docker container built successfully.

My son opened the browser. “That’s actually our site.”

Not a template. Not a theme. Our site, built from our specification, running our design.

“Can we deploy it?”

“Push to main branch. GitHub Actions will handle the rest.”

He pushed. Three minutes later, mysimrig.nl showed our homepage. The failed brackets from my 3D printer still sat on the desk, but we had a working website.

“How do I add products?” he asked.

I opened VS Code. Created a new file: /src/content/products/stuurwielen/fanatec-csl-dd.md. Added the frontmatter. Typed the description. Saved. Commit. Pushed.

Two minutes later, the product appeared on the live site.

“That’s it?”

That’s it. No admin panel. No database. Just Markdown files and Git commits. Exactly as specified.

What actually ships

The AI hadn’t built what we dreamed. It built what we documented. The difference between those two things determines whether you ship a product or a story about why you didn’t.

The realization

The next morning, I walked in to find him already at the computer.

“I broke the carousel,” he said, grinning.

“How?”

“I wanted the slide transition to be faster. I found the config file, changed duration: 500 to 200. But now it looks twitchy.”

In the Wix days, this would have been a dead end. A blocked feature. But he wasn’t staring at a “Contact Support” button. He was staring at text.

“So change it back,” I said.

“I did. Then I asked the AI why it was twitchy. It told me to add an easing function. Look.”

He spun the laptop. Smooth, snappy transitions.

That was the moment the penny dropped. He realized that src/content/products wasn’t code he needed a degree to understand, it was just a filing cabinet.

And the 4,847-word specification wasn’t homework; it was the instruction manual he had written himself.

He wasn’t just a user anymore. He was the maintainer.

The Digital Pit Crew

That afternoon was six months ago.

Today, MySimRig.nl isn’t just a static page with a carousel. It is a platform.

The “Custom FOV Calculator” he dreamed about in the doorway? It’s live. Along with five other tools, including an ideal racing line simulator that eats CPU cycles for breakfast.

We’ve partnered with ten major sim racing retailers. But the part that makes me smile isn’t the traffic; it’s the workflow.

We didn’t stop with the builder agent. Because the foundation was built on clean text files rather than a complex database, automation became trivial.

We have since assembled a “Digital Pit Crew”, a suite of background agents that now handle the grunt work. One monitor prices across our partners, another aggregates sim racing news, and a third handles translations.

The 4,847-word specification didn’t just build a static website; it built an autonomous operating system.

And my son? He isn’t fighting with drag-and-drop editors anymore. He isn’t shouting about broken layouts.

He’s busy interviewing well-known racing drivers. He’s sending invites to industry legends. He’s running the business, not the div tags.

The 3D printer in the corner still fails occasionally. My office still smells like burnt coffee. But the grievance is gone.

We replaced the frustration with specification, and in doing so, we didn’t just build a rig. We built a runway.